“It was the devious-cruising Rachel, that in her retracing search after her missing children, only found another orphan.”

Quite apart from anything else, the past — even the very recent past, maybe especially the very recent present — is a mass of detail that’s hard to take in and process (not least because you have to push away the immediate present to do so). My conference produced a little over 12 hours of conversation in one large (often quite hot, by the end quite airless) room, and the discussion has continued elsewhere, in nearby pubs or bars after the two days of debates; also here at ilm, here at Freaky Trigger, and here and here on tumblr. Resonance 104.4FM broadcast it nearly in full on 25 May and have put the eight extracts up on their mixcloud site here (I don’t know how long for).

Quite apart from anything else, the past — even the very recent past, maybe especially the very recent present — is a mass of detail that’s hard to take in and process (not least because you have to push away the immediate present to do so). My conference produced a little over 12 hours of conversation in one large (often quite hot, by the end quite airless) room, and the discussion has continued elsewhere, in nearby pubs or bars after the two days of debates; also here at ilm, here at Freaky Trigger, and here and here on tumblr. Resonance 104.4FM broadcast it nearly in full on 25 May and have put the eight extracts up on their mixcloud site here (I don’t know how long for).

If I say the commentaries so far have been partial, I mean three things. First, that several of the commentators (Tom Ewing and Hazel Southwell in particular) are very good friends, co-conspirators even; they’re partial to me! Second, that with a couple of exceptions, almost no one commenting attended the whole thing: I actually agree with plenty Laura Snapes says, but she was only in attendance for her own session; purely as a description her account can only reflect that final 100 or so minutes (and the fact that she definitely had the pointy end of the Q&A, in the jaded final minutes of a long tiring day). And third, so much seemed to be touched on over the two days that wasn’t pursued, as is the nature of these events; certainly it’s going to take me a long time to dig down into what I actually now feel, less about the conference than about the era it claimed to explore, what this era meant and means, and why (or indeed if) it still matters at all. On the whole, I’m enormously pleased with how it turned out, just because I think such a lot has been gathered together and set down for future scholars and scoundrels to play with. (Transcripts of the panels are to be gathered into a book along with further memoir and commentary by those who attended and those who couldn’t: this is the plan, anyway. Though I’m taking a bit of a break first.)

Here’s an extract from the report I wrote for Birkbeck:

Underground/Overground:

The Changing Politics of UK Music-Writing 1968-85

This was a two-day symposium (15-16 May) at London’s Birkbeck Institute for the Humanities, consisting of panel discussions and Q&As. Run by Mark Sinker, former editor of The Wire, it brought together writers, editors and readers of the underground and trade music presses of the 1970s and 80s, to explore their own experiences academics and other media commentators. The first day looked at the period when UK rockwriting emerged out of the conflict between a rising generation’s counterculture and the embattled establishment in the late 60s and early 70s. Through the witness testimony of participants, and the overview of historians of the era, panels examined the evolution of a critical outsider voice in the UK, as inflected through the rock papers between these dates. We learned what the underground press felt like to write for, how the mainstream press responded to rock music and its social penumbra, and how the trade press reached out for some of these writers — notably Charles Shaar Murray, who had written for the notorious schoolkids issue of Oz as a schoolkid — and what it was like moving over to the trade press. We heard from those in the editorial backroom about what it felt like being on a weekly responding to stories in pop and politics, how decisions were made and what the pressures were: Cynthia Rose noted that this was a time when striking miners’ wives from Kent came to the NME office to discuss stories run on them.

On day two, we heard more from voices outside these offices and these times, as a kind of counterpoint to the more canonic stance perhaps established on the first day. Val Wilmer, a veteran of the music papers in the 60s, recounted what it was like as a woman — in the very male milieu of jazz writing— bringing back stories from the radical black underground. There was a panel exploring punk’s often difficult relationship to the underground that helped birth it, and another on those constituencies not so well served by the music papers at this time, looking at black music and dance music especially. Finally a somewhat turbulent panel attempted to answer the tricky question of legacy — how much does this history help or even affect writers today?

In the course of the two days, we heard from well known voices but also from people who have not often had the chance to enlarge on their perspective. An enormous amount was touched on that will be of interest to scholars in various fields, from popular music and media studies to sociology and political aesthetics. Some myths were exploded, others perhaps further entrenched.

One thing I always hoped to do as an editor — and it turns out being a conference runner is not dissimilar, in its joys as well as its frustrations — is to bring voices together that didn’t normally get converse in the same space: as at The Wire in the early 90s for a couple of years, so at Birkbeck in mid-May 2015 for a couple of days. In both cases, I was especially keen — as discussed in this earlier post — that the past and the present creatively encounter one another, perhaps on slightly different terms than they do ordinarily, in music-writing or anywhere else. So as well on critical writing on the various contemporary streams, rock and pop and soul and rap and dance and the electronic avant-garde, blah blah blah, I following my predecessor Richard Cook in deliberately encouraging contributions from the best voices from the old guard, voices talking about (at that point) some 70 years of jazz, and some nine centuries of composed music.

Did I succeed? At the time I thought no: I felt that this particular exchange, between the best of the present and the best of the past, was still a dialogue of the deaf. Few in the various territories I was yoking together seemed at that time curious enough to explore the interests of rivals sympathetically or insightfully. And of course in practice The Wire had a super-tiny budget, and our bat-signal was primarily attended to by those with nowhere else to go when they wrote on x or y, the high quality of their commentary notwithstanding. Writers who are experts in their own specific (sometimes small and embattled) fields tend to hunker down and play defence when they encounter enthusiasts for very different fields and tendencies and perspectives.

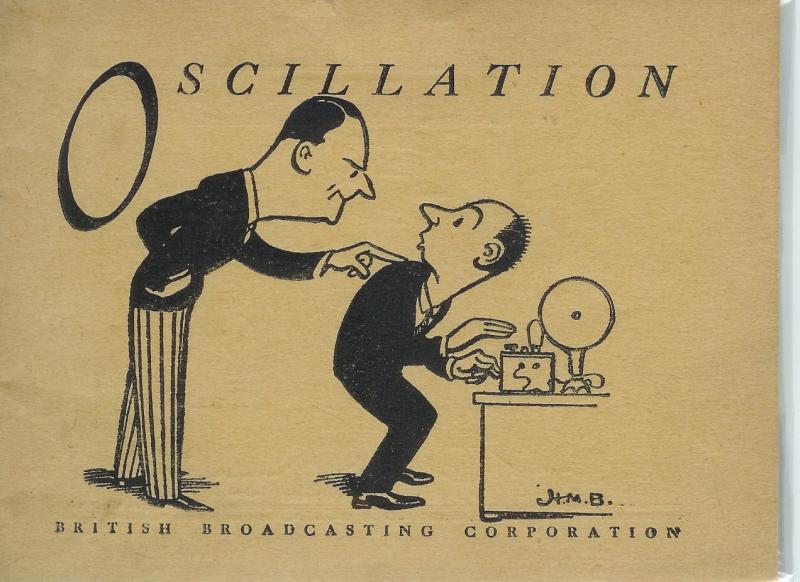

Then again — for this or other reasons — I wasn’t editor for very long. Because the ways to combine the perspectives, or use them creatively against one another, are generally worked out by readers, not least when or if they in turn become writers a few years down the line. An editor’s job is ultimately — in various different ways — to be a kind of idealised reader. And one element of this ideal is the plain fact that readers can enjoy a piece by one writer, and get a lot from — then turn the page and do the same with the first writer’s mortal scornful foe. From the thread discussion that hangs from Tom’s FT review, a theme emerges that I absolutely recognise, summed up by a useful word that hadn’t occurred to me: “oscillation”. Just in the territory the conference covers (but also in my conception of the role of The Wire in the early 90s), there seem to be a proliferation of essential oscillations between this or that or the other opposed cultural ethos*. Not just the way rock rubs against jazz on one side and pop on the other, and punk likewise; not just (as Frank Kogan notes on the FT comments thread) the way critical journalism rubs against investigative journalism, or the way that both rub against history; not just my overall theme of underground and overground, and how inside track and outside pressure work against one another; but the ancient uneasy dances of music with noise, and of order with desire; and of course of age with youth… If “1968-85” is my shorthand for the era of the self-consciously all-encompassing ‘outsider’ magazine [adding: in the UK] — “1968-94” only if you include Richard’s and my time at The Wire — then this is the era when technology and happenstance combined to fashion a clustered territory where readers were encouraged to enjoy and think about conflicting things; to move backwards and forwards between stances and traditions, in and out of close-read trust as they turned pages.

The potential of this world arose from the richness of this dividedness: and the refusal of any of the divisions to map simply onto the economic or racial or gender seperations and hierarchies that structure the larger world. And underneath — or above? — all these is the refusal of the not-quite division of music from the spoken or written world to settle into anything easily summarised, whatever the fashionable pressures of niche-marketing at target demographics. On one hand, all the splintered and shifting currents of music present a map of the real in its infolded complexity; on the other, there’s no music that doesn’t also manifest as a rhetoric of potential utopian togetherness: on one hand, there’s just the fact of the unpredictable constituent shape of any gathered crowd at any show; on the other, the potentially mutable readability of music itself, its last-instance combination of concrete sensuous quiddity and, well, untranslateability. We may occasionally agree what the words of a song mean, but all we can actually agree we agree on in the bits of music that aren’t words (i.e. re the meaning of this harmony, that chord change, this blue note, that grace note, this fill, that grunt…) is that we likely don’t agree. That’s the point: we’re gathered here together in part because we like that we won’t read it the same, and that’s the fun and the risk.

(Unlikely and probably unsustainable analogy: the Bible shared in a shared language you mostly didn’t understand enabled religious unity; however — and Lollardry notwithstanding — the Bible translated into a shared language you DID understand meant a splintering into warring sects…)

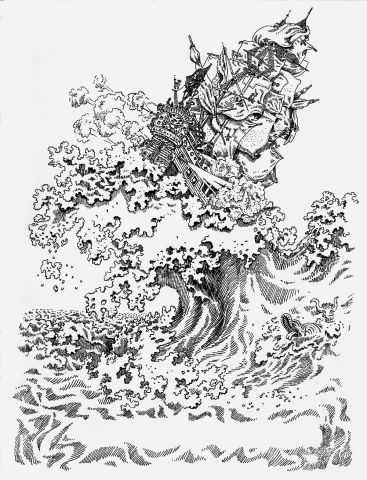

The panel I was secretly most pleased to have convened — because it dug into the kinds of backroom work that people who never worked in print-age newspaper or magazine offices rarely understand, however closely they’ve read the output — was the final one on Friday, which Tom ran: The encroachment of professionalisation on a generational playpen — What were the pressures in a music paper’s editorial office, and what was the potential? Half-joking about the working conditions, Cynthia Rose used the term “plantation journalism”: the papers themselves were really make a LOT of money, but little of it reached the editors and stringers, hired to deliver a Stakhanovite output day after day (these were cheaper times to live, for sure, but there was still no margin to put by even a penny of every pound you earned). Tom reaches for a rather different metaphor: “… [T]he sense of the work on an underground or weekly mag – the circus of sheer effort involved in bringing the bastard to land each week, that was grand to hear about, like a hundred years ago you might have heard men talk about life on a whaler…” This was a small, shared world, baffling and perhaps worse to those who come long after, beleaguered by surging pressures but united by task into intense group loyalty, its reward mainly a very local prestige, with (lurking at once just over the horizon but also, unmentionable, within the crowded quarters) the terrific Moby-Dick shaped leviathan of, well, what, exactly? The implicit politics of the craft of this long-vanished music-writing worldlet?

There are plenty of other very smart things that could be quoted in that thread. But this is me writing, so right now instead I’m going to quote myself, because I think this is relevant: “We live in a time of extremes of proximity, not just between cultural blocs formerly more safely distanced (or so it seemed, in the metropole), but also between present and strong representation of elements of the past […]: I think negotiating these proximities has become a *lot* more perilous, but we actually do have to negotiate this situation (and not just wish it away as a symptom); which inevitably means become expert in far more things than we perhaps formerly believed we signed up for.” The internet has collapsed distances, and not just between the many militant faiths and political stances as they exist in the once-wide world today: we are more than ever, every day, hard up against idealised echoes of the past, and more than this echoes of various rival idealised pasts, making very strong demands on us. We castigate those who wish to return us to such-as-such a point in the past — arguing (generally correctly) that they have no strong sense of what it was actually like — and then we turn round and lament that such-and-such an organisation or institution is not what it was, and will only return to relevance when it rediscovers and reanimates its earlier principles and purpose. At which moment, others naturally castigate us. In other words, how we address and draw from the past is as live and tricky an issue as it’s ever been: even “where’s that jetpack I was promised!?” is an appeal to a past mode of futurism. As time passes, revolutionary purists more and more become original-intent reactionaries: one thing we ought to have learned from punk is the inextricable tangle that year-zero vanguardists get themselves into as they thrust us to the future: “rip it up to start again” is an intrinsically conflicted demand…

A conference organised to cover 1968-85 can (just about) get away with being eight panels and roughly 30 people: probably not representative of those involved, but not quite out of sight of it. As Hazel said to me at some point, how would you even begin to select people represent the last 15-odd years? You’d need 20 panels with 50 people on each. An ocean so full of vessels, and indeed wrecks of vessels… In their physical and structural make-up, the seas we sail have changed utterly. To quote myself again (this time from a 2009 essay for a collection on Afrofuturism that rather irritatingly still hasn’t appeared: A Splendidly Elaborate Living Orrery: Transplanetary Jazz: Further Thoughts on Black Science Fiction and Transplanetary Jazz):

With the internet, the discursive cosmos can seem inverted, matter for emptiness, emptiness for matter: a multitude of isolated geocentric bubbleworlds, planets and asteroids dragged into their neutron gravity, the heavens become a dense, grinding press of shattered astral matter… Encounters are still possible: to tunnel to this or that bubble isn’t rocket-science. But no gorgeous sunflare or night glow through velvet dark to call us, magnets to the romantic eye all broiled to cinders. And history — that painstaking reconstitution of real-time fragments — seems harder than ever. Stargazing has become a shuttered archeology of the hardscrabble crystalline sky.

A friend who sat though the whole thing, both days, described it afterwards as being the tale of a long battle utterly lost. And half of me sadly says yes to that; and half of me stubbornly thinks no. In practical terms, of course we can’t reinvent the music-press of the 70s and early 80s: it was never less than a curious serendipity, a confluence of a great many unrepeatable things; it was rooted in technologies that no longer exist and a society that has very much mutated. As a format, it was as highly unstable as it was path dependent: it didn’t make much economic sense, and very few writers made their fortune from it (a few made their fortunes escaping from it). Maybe for a while it was possible for a select few, with the right gifts but also the correct attributes, to make an inexpensive living from it (which I never did; my entire working life I’ve made my living basically correcting other people’s spelling). Many many people were unable to break into that select few — I made a point of inviting some people who were outsiders at the time, even if they momentarily had their foot in the door; who don’t ordinarily get to join in the retrospectives. There’s no dearth of good writers today, that’s not the problem at all (OK don’t get me started on good editors). But we haven’t found a way of making the current set-up pay for itself, in a way that’s remotely fair to the majority of the writers battling their way through it.

But it was also always after all a tale of the belief in the benefits that accrue by unleashing the unlettered urchin glee of the young on the wider world — on cultural legacies till then beyond their ken — and then battling with the problem of how things fell out when this wider world, as it always did and always will, began (a) to return the not-unpoisoned compliment, and (b) to include the past. As for (a), the urchin cheek now flows both ways, and now and then respectful tact flows with it also, and the two are needed, going in both directions, for adult relationships to survive that that aren’t lifeless or toxic reverence.

But (b) is much tougher to trust in — the past only ever has unbiddable parity when it manifests as a stony unchanging weight, the return of the dead as a forbidding monument. Yes, perhaps the designated crew can journey out to it the way we did with Afropop in the 80s or KPop over the last few years, with care as well as insolence, with fannish fascination as well as straightforward well intentioned inquisitive ignorance — but with Afropop and with KPop at least there was potentially a case that a similar counterflow might push back, to challenge the errors and rude liberties taken. That the implicit problem of “who’s this WE, white man?” could one day dissolve or transform in the encounter, to everyone’s benefit. But how can the past push usefully back in like fashion?

But (b) is much tougher to trust in — the past only ever has unbiddable parity when it manifests as a stony unchanging weight, the return of the dead as a forbidding monument. Yes, perhaps the designated crew can journey out to it the way we did with Afropop in the 80s or KPop over the last few years, with care as well as insolence, with fannish fascination as well as straightforward well intentioned inquisitive ignorance — but with Afropop and with KPop at least there was potentially a case that a similar counterflow might push back, to challenge the errors and rude liberties taken. That the implicit problem of “who’s this WE, white man?” could one day dissolve or transform in the encounter, to everyone’s benefit. But how can the past push usefully back in like fashion?

Journalism, including cultural journalism, is of course primarily about the now — it’s called NEWS for a reason. And part of working out what’s actually significant now includes a recognition of the relevant force and quality of the various flows. I’ve paid tribute to these music-magazine and weekly paper offices of long ago because — by the serendipity of the times — they saw a coming together of writers and editors from very different backgrounds, responding to very different calls. And that’s part of the complex, contradictory weave that I value, or mourn, if that’s the appropriate word. But now I think of it, the best of the writing exhibited the same characteristic: every writer’s indiviudal style that I admire from then (and also now, because this hasn’t vanished) was and is a crackling codeshifting weave also, of threads that come from very different sources. (Because good writers are always readers, and these were always wideranging readers, and listeners too…)**

And as codeshifters get older, their involvement to history — the one I’m obscurely worrying at throughout this rambing post — of course grows in and out of their relationship to their own youth; to their memory; to the values they set out with long ago; all this is bound into what they do and who they are. And some people settle into this badly, because they can shift themselves into a place of comfort and shallow complaisance. And others, well, others find they’re always already been embedded in a world that has cultured such negotiations and such oscillations reasonably effectively: they maintain curiosity, self-awareness, self-irony, amusement, kindness, anger, the ability to manage simultaneous contradictory status and pressure and pull. The trapdoors and the timebombs, they’re coded right into us, if we know how to listen — and of course we learn to listen to our inner pirate crew by learning to listen to others; others often not at all like us, insofar as we’re even like ourselves. How we address the popular, how we prioritise the semi-popular, how we respond to the unpopular or the plain unknown, these are ever-more linked into our relationship to the past, recent or deep: and this is not going to change; if anything it’s going to intensify.***

*The world seems to be divided on what a correct plural of the noun ethos is: ethe or ethea or (the incorrect but greeky) ethoi or (the anglicised but silly) ethoses. In the mood of the moment, I choose to take this to be telling…

**I’m going to defend the mixedness of this overall metaphor as further evidence of what it is I value: gallimaufry, salmagundy, macaronics: pie itself gets its name from the mixed jumble of items found in a magpie’s nest…

***There’s a peril in dredging up the carcasses of the vessels of the past, and probably more than one, especially if you do it collectively. Collapsed across the treasures you hoped to re-acquaint yourself with is the bony evidence of crimes you’d hoped perhaps to forget, and so on. But the discussion of all that is for the future, now, when the book starts to be made. For now, I want once again to say a powerful and heartfelt THANK YOU to everyone who participated and attended, and advised or helped in ways large and small. It was what it was, and what it’s going to be, who can say?